In June 2008, I had to ask my grandma to fake death.

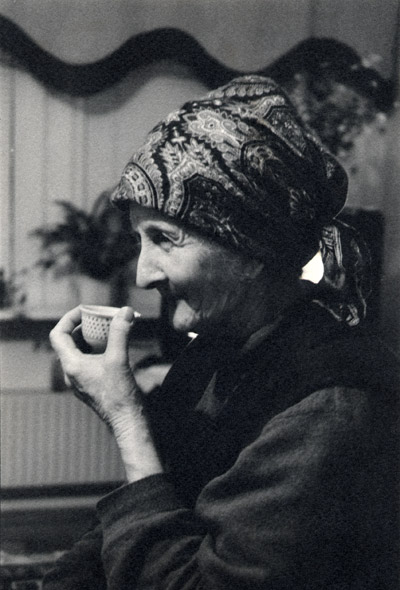

Although she shouldered some eighty years, her back was stick straight, as if always at attention. I have never seen her slouch in front of a TV like every single one of us from my father’s generation on. She had the liveliest eyes and rosy cheeks as if she’d pinched them a little too many times back in the day when grandpa was trying to get her to marry him. I suppose they had to be quite red to knock him off his feet when she peeked out through her window, with only moonlight to play with. I never figured out her toothless smile. It made her look either shy or smart. She hated commotion and conflict, and she read he Qur’an deep into the night and early in the morning and on hot afternoons in her cool corner where the light was good and where her eye-drops had their proper place and where she hid her blood-pressure pills. She was quite blind, and deaf. She would sit ten inches from the TV-set, watch it from it side with her good eye, and with her good ear turned to the left speaker. She had broken her left hip some twenty years earlier and now that she was living in modern Sweden since the outbreak of the Balkan war, she still refused to have it fixed, properly this time. Needless, you know. Her name is Sena Mahmutović, and I had no idea how much she loved me.

In Spring 2008, while my American colleagues at the Department of English, Stockholm University worried who would be the democratic candidate – Obama or Clinton) – and whether or not either stood a fair chance in the upcoming elections, I walked about thinking how to ask my grandma to fake death.

Why?

For a film.

I always wanted to make a film. I tried pulling together a project a few years earlier, but no Swedish producer wanted to risk being ripped off by those Balkan types, by which they did not necessarily mean me, but the people in Bosnia where I wanted to shoot it. And the story I had in mind was too … outrageous, I suppose.

Now I had a much simpler story I called “Gusul” which was about two Bosnian immigrants in Sweden, a sick mother and her only daughter, living alone after the father/husband was killed in the war, which reduced the old woman to a silent, supine body. Then, the only time the daughter hears her mother speak, is when the mothers asks her for some traditional plum pie, a very curious kind of dish that is really nothing like a pie. This seems to be a sign of recovery, but then the mother dies, and the daughter decides to perform the Muslim ritual washing, gusul. One last touch, one last intimacy.

An old friend of mine, Armin Osmancević, who ran an advertising agency WERK and a small film company called ARTWERK, proposed that he produce it. The story conveyed an immense intimacy between the women, and Islamic sentimentality quite uncommon in contemporary fiction and film, far removed from controversial and hyped-up bullshit.

Armin put together a team of people as diverse and culturally unconnected to some elements of the film as possible, but each cared about the kernel story. They all worked for crumbs. Our budget was small and meant to cover the equipment, and the lead actress Aida Gordon, who would come to give an amazing performance for half her usual rate. But we still needed to cast the mother character.

I could not imagine anyone more perfect than my own grandma, but how to ask. She was a traditional woman, wearing a hijab even though she had been in menopause since time immemorial and did not have to. I did not only need her to fake death but also to strip naked to get the ritual washing.

I could not do it, so naturally I told my mother, who told my grandma, who in turn said, Yes.

No hesitation. Just a Yes. Plain and uncanny.

I got this feeling of electricity crackling on the surface of my skin, and my lungs heating up. Yet, I still had my doubts whether or not she could really make it happen. Did she really understand what she signed up for? Again, I told my mother, and she asked her, and she came back with the best answer.

The shooting was postponed from June to September.

When we finally had a date that suited everyone, 12-14 September, it coincided with Ramadan, the holy month of fasting, when Muslims skip eating from sunrise to sunset. September days in Northern Sweden are long, 4am-8pm. I told Grandma she was old and weak, not in her best health, so she should not be fasting. I said, “You’ve done your share of fasting and it’s plain irresponsible to put such a strain on yourself.” But no, she had done it since a young girl, and she was determined to keep fasting Ramadan until she died. She would not stand us up, nor would she stand God up. It was her first role. She was curious.

I do not want to complain about the ordeals of preproduction, and as an afterthought I do not care about the Hell of postproduction with burnt hard drives and mission-impossible rescues of the material, and the CGI of grandma’s twitching eyes while dead. It is the three perfect days of shooting that are the best days of my life.

Grandma lived with my parents in a city some 200 miles south of Stockholm. I asked her to bring all the pajamas or whatever she used to sleep in, so we could see what color was most suitable. She said she had nothing new and fancy and she feared everyone would laugh at her for that. That was not exactly what I imagined she would be worried about. She had further worries her hair would be messy and unmanageable, that she would forget her cues, nothing unorthodox for any actress.

On Friday 12, we hired the equipment, and my parents brought grandma in the evening. After dinner, I walked her through the script, and was quite hoarse afterwards. She was deafer than six months earlier. She did not show a trace of doubt that the film should be made and that she was the one to do the “dying” job.

On Saturday, the first day of shooting, I forgot the keys to the apartment we would be using, so the crew had the breakfast meeting on the sidewalk waiting for me to fetch the keys. The apartment was my mother-in-law’s, a simple immigrant abode, run-down just enough for the pathos of the story, but it had big windows and we wanted a lot of natural light flooding the stage. My father-in-law, who was cancer sick, spent the weekend at my place.

Aida Gordon, the actress playing the daughter took time talking with Grandma, and making a great first impression. They charmed everyone, and created the perfect atmosphere of warmth on a cold Swedish morning.

Grandma spent twelve hours in bed, getting up for occasional visits to the bathroom. The make-up, camera adjustments, lights, props, all that took an awful long time. The shooting was quite quick. Grandma was anxious about wearing make-up, because she had never used any such thing. The Swedish make-up artists, who were paid in movie-tickets for the film festival, explained to her it was not really a whole lot of mascara, eye shadow, lipstick and all that jazz that she needed. She only needed some cover that killed the sweat flow, and consumed light rather than reflected it.

Grandma’s lines were the funniest. I lied on the floor, out of sight, and prompt her, and sometimes when I tugged her sleeve or something, she’d say, What do you want? Although she knew she was only acting, she took everything literally. When we practiced, I told her she should say, My feet are cold.

She got serious and said, Yes, that’s true, they are cold, all the time.

Then, when we the camera was rolling, and I prompted her to repeat the words, she said, Now they feel warmer.

She did not quite understand why she had to repeat the same words over and again as we were shooting the same scene from different angles, or when Aida did not get the scene just right.

In another scene, we wanted her to drink water, or just pretend to take a sip, and say that she wanted some traditional Bosnian plum pie.

She said, I’m fasting.

I said, You won’t eat it, just say you desire some.

But, I don’t want any.

Just say it.

All right.

Now, she knew that first thing that morning we had already filmed the scene when the daughter makes the pie. She said, But she already made the pie, she doesn’t have to bother making another one.

We wanted the actress to prepare for the scenes where she is immensely sad and tearful, but Grandma kept saying things that made everyone laugh, and as the shooting went on there was an expectancy that she would keep delivering these lines that would do well in behind the scenes footage. There was none such footage, of course.

We wanted the actress to prepare for the scenes where she is immensely sad and tearful, but Grandma kept saying things that made everyone laugh, and as the shooting went on there was an expectancy that she would keep delivering these lines that would do well in behind the scenes footage. There was none such footage, of course.

On Sunday 14, the fake death day, when we planned on filming the scenes of ritual washing, I only slept a few hours. I got up at 4 a.m., drank a lot of water and carrot juice, but I could not eat. I too would be fasting. I sat scribbling on my laptop, and watched the sun play with old roofs of Stockholm churches across the narrow strip of sea between Skanstull and Hammarby Sjöstad, waiting for Grandma to wake. I could not stand waiting so I went out for a run, imagining I fell into the cold, harbor water, getting out all cool and fresh, between boats and wild-duck droppings, the drowsy seagulls, swans and those red-beaked black birds I never cared to find the names for. I kept thinking about Grandma and what she was doing for me.

Grandma was tired, and hoped we could finish her scenes quickly so she could go home. I did promise her she would not have to work more than one day, but I underestimated the need for rearrangements, rehearsals and retakes.

She had trouble mastering the art of keeping still when she faked death, but otherwise she expressed no anxiety. I so wished to know what was going on in her mind, and yet not. I kept at her side as Armin was directing. She had no more lines to say, which meant she would not make any funny mistakes, and that made the washing scene even heavier, but at the same time she did peek or wink or sneeze or sniff or lick her lips or asked questions about the guys hiding behind lenses or microphones or lights. Ergo: many retakes.

She was done by 4 p.m. dressed up and eager to go home.

I wanted to buy her something, a small token, anything.

She refused.

I insisted.

She laughed at me and slapped my on the chin.

I told my wife to find her some nice clothes, a new skirt, pajamas, blouse, anything. My wife thought Grandma had trouble walking in long skirts, which got tangled up all the time with her walking aid, or when she sat in narrow cars. She bought her a pair of really nice, soft, and comfortable pants. She refused to even try them on. She said, I’ve never worn pants in my life and I sure am not going to start now.

Then she left. I went back to the set, thinking of her.

We had a telephone scene left to shoot, when the daughter squabbles with the imam about doing the washing at home. I could not focus. I ate the rests of the plum pie.

(The official website Washing).

Oh! so good to see you back *smiling* — I hope to catch up today and look at what you sent, unless it is too late – I hope by tomorrow to do that….*mwuah* good friend.

I love her too! she’s just so mellow and fragile, yet the strongest woman you can think of!

Now that is a film I would love to see! When and where can I see it?

/Urban

Urban, if you want, give me your email and I’ll tell you when it’s done. We’re dealing with some sound editing difficulties right now. I’m glad you’re interested. Do get in touch adnanmahmutovic@yahoo.se

This essay is simply extraordinary, Adnan. I would very much like to see the film, when it is done – but also – is the story in existence as a piece of writing?

Thanks Vanessa. I’ll send you the film once it’s finished. There is a story, still unpublished. I never sent it anywhere, it kind of struck a cord in the guy who directed the film and he asked for a screenplay, so everything took that course. I should send the original story out there, I think.

Great account of the shooting, felt like I was there. Each person is vivid in your words. Intriguing! Did you write the script?

Thanks. Yes, I did. It’s based on this story: http://www.roseandthornjournal.com/Spring_2011_Prose3.html

You can find the film in two parts on youtube